This is a chapter originally published as:

Ramos, J. (2016) The structural, the post structural and the commons: meta-networking for systemic change,In Pease B., et al. (Ed)Doing Critical Social Work, Allen and Unwin

Introduction

This chapter takes up the challenge posed by the editors of this volume, to articulate new forms of critical social and community work thinking and practice which engages both with the need to provide conceptual leadership in transforming existing structures and institutions, while simultaneously providing openings for conceptual diversity, interpretive multiplicity and opportunities for agency (Briskman et al 2009). My work has focused on global problems which affect most countries today, namely: challenging neo-liberalism and articulating alternatives to it, the co-optation of political power by moneyed interests and the need to strengthen democracy, the problem of social atomisation and consumerist driven individualism and the need to develop peer-to-peer and solidarity cultures, and the ecological crisis and the need to create ways of living which are in genuine balance with our integral life support systems. As might be recognised from this litany of issues, my work and research, initially connected to the World Social Forum but now with a variety of communities, has been typified by conditions of high cultural and conceptual diversity (Ramos 2010). Because of this, my work has simultaneously engaged with both the question of developing agency that can create and transform global structures and systems, within communities in which there are a wide variety of interpretations on what those structures are, and diverse visions for change. This chapter provides an overview of this work from both the inner (or epistemological) dimension, and outer (or ontological) dimension of the practice. This practice can be described as ‘meta-networking’ for systemic change.

In this chapter I therefore argue for a social work practice which integrates the structural and post-structural nature of the challenges and issues people face in addressing many commonly held social problems. Rather than accepting that diverse social perspectives are mutually exclusive, meta-networking offers an approach that can lead to the capacity for diverse actors and agents to collaborate on solving common challenges. Reflecting Jim Ife’s (2012) core argument that social and community work needs to be coupled with a strong ethos of shared humanity and more extensively cultural forms of human rights, I argue the integration of structural and post-structural strategies through the practice of meta-networking is a pathway toward developing a practice that can develop the social ‘commons’ and common good at many levels, an approach fundamental to social work in the 21st century. If critical social work is to address the origins of social problems through systemically intelligent change strategies, meta-networking should be a key approach in the critical social work tool kit.

What is meta-networking?

Meta-networking is a process by which people work to create networks which facilitate flows of information and allow coordination and cooperation between otherwise disparate groups of people, with shared interests but with differing perspectives.

Meta-networking involves the linking or associational formation of disparate actors into a network, with the aim of helping the constituency to develop and meet its goals. It can be located as both a social research practice (Chisholm 2001) and an approach to community development (Gilchrist 2004). Trist (as well as Carley and Christie) were early developers of the thinking and practice of inter-organisational network development (Trist 1979, Carley 1993). Gilchrist locates it as a core community development practice and role, while Chisholm argues it is a type of action research.

Carley and Cristie describe inter-organisational network development aimed at sustainable development through ‘action centred networks’. These use network strategies to solve complex sustainability dilemmas (Carley 1993, 180). In their approach to ‘human ecology’ and ‘socio-ecological systems’, they argue that ‘meta-problems’ are at the heart of many of the modern problematiques we face:

‘metaproblems both exist in, and are the result of, turbulent environments which compound uncertainty, the root of the word problematique’ (Carley 1993, 165).

This era’s meta-problems overwhelm the capacity for single organisations to cope with the challenges they face. What is required, they argue, is the development of ‘action centred networks’ that develop ‘connective capacity’ and undertake ‘collaborative problem solving’ (Carley 1993, 171). These networks can offer a variety of solutions; regulation, problem / trend appreciation, problem solving, support, political / economic mobilisation, and development projects (Carley 1993, 172). They argue for ‘linking pin’ organisations – organisations that provide a structure or platform for communication and coordination across groups, and thus can become a network of networks (Carley 1993, 172-173).

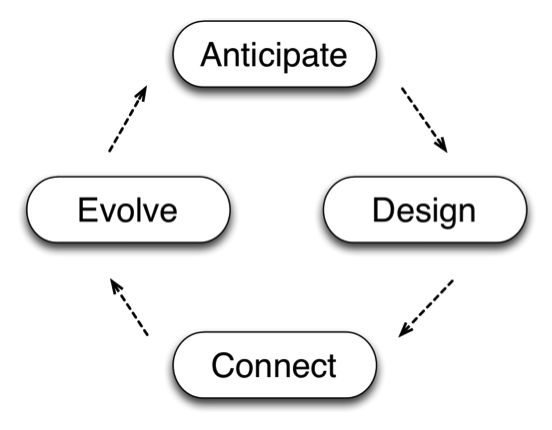

They argue that if potential conflicts within action centred networks are properly managed, such networks can lead to the capacity for innovative responses to meta-problems collectively faced. This innovation requires linking ‘anticipation’ (drawing from Godet’s ‘La Prospective’) with collaborative mobilisation and practical and strategic action. They specifically called for approaches that develop such action centred networks (Carley 1993, 180-181). Trist (1979) argued that ‘referent organisations’ were a critical aspect of meta-networks in providing leadership for a domain:

Once… a referent organization appears, purposeful action can be undertaken in the name of the [meta-network] domain. To be acceptable the referent organization must not usurp the functions of the constituent organizations, yet to be effective it must provide appropriate leadership. (Trist 1979, 9)

Meta-networking as pathway to the commons

My research area on the World Social Forum (WSF), spanned a decade from 2001 to 2011. Early on, from 2001 – 2004, I saw the gathering at Porto Alegre as an emerging ‘counter hegemonic block’, where various civil society organisations would unite in common solidarity. This idea (originated by Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci) contained the proposition that revolutionary change is preceded by a form of cultural activism – that is, when the key cultural institutions, churches, social organisations, etc. come together in a coherent opposition to a dominant consensus or ‘hegemony’ (a ruling order), change then follows (Hansen 1997). I therefore hoped that with time, the various actors, organisations, activists and people brought together in the World Social Forum, would ultimately work through their differences, and come together in a strategic and ideologically coherent relationship. At the time George W. Bush was in power and the United States (US) invasion of Iraq – initiated on the false pretext of weapons of mass destruction – was in full swing. The connection between those with great political power and corporate / big oil seemed to be converging to satisfy each other’s primal interests. It seemed at the time that, with the veil of corporate imperialism lifted for all to see, the 100 000+ people attending the forum would be united in opposition, if not in a shared project to create an effective alternative to the problem.

In Australia, Social Forums were held in the major cities, and I was part of the organisation of the Melbourne forums, five of which were held between 2004 and 2010. In the seven or so years studying social forums and communities, fundamental assumptions I held were challenged. The idea of a Gramscian counter hegemonic bloc made less and less sense in the face of participant diversity, indeed radical diversity, and the very different images of the future (of alternative globalisations) that were held by participants. In my quest to understand the various images of the future that a variety of different activist organisations and non-government organisations (NGOs) held, or what Castells (1997) termed the ‘telos’ of a group, I found that the discourses and visions that mobilize various actors in such events were not so easy to combine. While concerned scientists, peace activists, eco-feminists, re-localists, socialists, cosmopolitans, post-developmentalists and a variety of other mindsets converged in a maelstrom of discontent and radical activism, all which can be considered to be counter hegemonic (in their opposition to the dominant neo-liberal vision), the histories and strategic visions of the various groups were distinctive nonetheless. Understanding what was in play would require distilling and clarifying differences as much as creating conceptual similarities.

In the process, Latour’s (2005) version of Actor Network Theory would be of great assistance, as it would show me that the way that a discourse frames the world does not just describe reality (the positivist view), but indeed it provides a template for strategic action for those who hold, use and disseminate a particular discourse or ideology (the constructivist view). As an organizer in such an event there was an aspect of letting go of the certainty of my particular frame of reference. I would need to listen beyond discourse, not just to discourse, but as discourse’s relationship to people and action. I would need to become a discourse mapper, practice ‘cognitive mapping’ (Bergmann 2006) as a way of coming to grips with deep conceptual and discursive differences, while at the same time keeping my eye on deeper connections and indeed the structural dimensions that brought us together as diverse actors. Thus, for an issue like climate change, there was no denying that a Greenhouse Mafia in Australia has systematically thwarted any significant political action for decades – collusion and the convergence of corporate and political interests, on a variety of issues, was well documented (Hamilton 2007). The structural nature of power, however, did not negate that critiques of power come from diverse perspectives and discourses, which frame both the present situation and the future differently. This is what Inayatullah (1998) terms as levels of reality, an acknowledgement that both the post-structural (language, metaphor and discourse) and structural (geography, culture, power, economy etc.) are all in play.

In this way I discovered that post-structuralism was a pathway to building deeper coherence and strategic action between a variety of groups that may not necessarily speak the same conceptual languages. This is where I slowly began to learn the notion and practice of meta-networking. The naïve belief that the world could be organized and neatly fit into a single ideological or conceptual frame of reference did not make for very good social and community development work. In the quest for social change I was required to engage with people with often very different pictures and narratives of our situation. However, as a group with common concerns, we still needed to be able to challenge and transform shared structures, but this was better done across the embodied experience of diverse people. The post-structural turn, to honour a variety of embodied ways of knowing, was a healthy and important step beyond a naïve structuralism.

Post-structuralism – an approach that could appreciate and leverage multiple discourses and worldviews – was important but not enough.. What was needed was inquiry toward a shared diagnosis of a problem, developing common ground vision and enabling collaborative collective action. The question remained over the why, what and how that brings us together – even when our discourses and perspectives differ.

In the World Social Forum and satellite forums (e.g. MSF) various actors, despite coming from often radically different perspectives, would collaborate to create change. Social theorist De Sousa Santos (2006, p. 168) thus argues that the modus operandi for the alter-globalisation movement (via the World Social Forum) is through ‘de-polarizing pluralities’. A pragmatic approach to diversity held sway, not by ignoring perspectives, but by making the diversity of thinking, what Santos (2006, p. 20) termed the ‘ecology of knowledges’, a resource that could be leveraged for co-analysis and collaborative strategic opportunities.

What emerged from this was an increasing appreciation for what brings us together despite our deeper differences. I have come to understand this through the language of ‘the commons’, as a keystone concept that may hold, if we construct it so, multiplicity and difference, but in dynamic relationship and synergy (Bollier & Heilfrich 2012).

Over the past ten years, I have been involved in a variety of processes that have taught me what it means to work across and integrate these dimensions of social and community work. The following account provides a brief overview.

The Melbourne Social Forum

The Melbourne Social Forum emerged as an expression of the rich networks of counter hegemonic actors in Melbourne. This included groups supportive of the WSF initiative, as well as groups and people who advocate or articulate for post-neo-liberal and post-capitalist visions. Initially, the MSF founding group was inspired by the shared experience of the Mumbai WSF in early 2004, that led to the first MSF in late 2004.

Social forums were co-constructs, in which forum organisers facilitated a process in which the ‘forum community’ came together. Without a community of counter hegemonic actors, there could be no social forum; yet without social forum organisers, there could be no social forums under the banner ‘Another World is Possible’. A collaborative field existed between different groups with similar attitudes and values, which generated ‘inter-alternatives’. A key form of agency was therefore collaboration among actors with a broadened conception of what a normative field meant – the aims and visions that guide action.

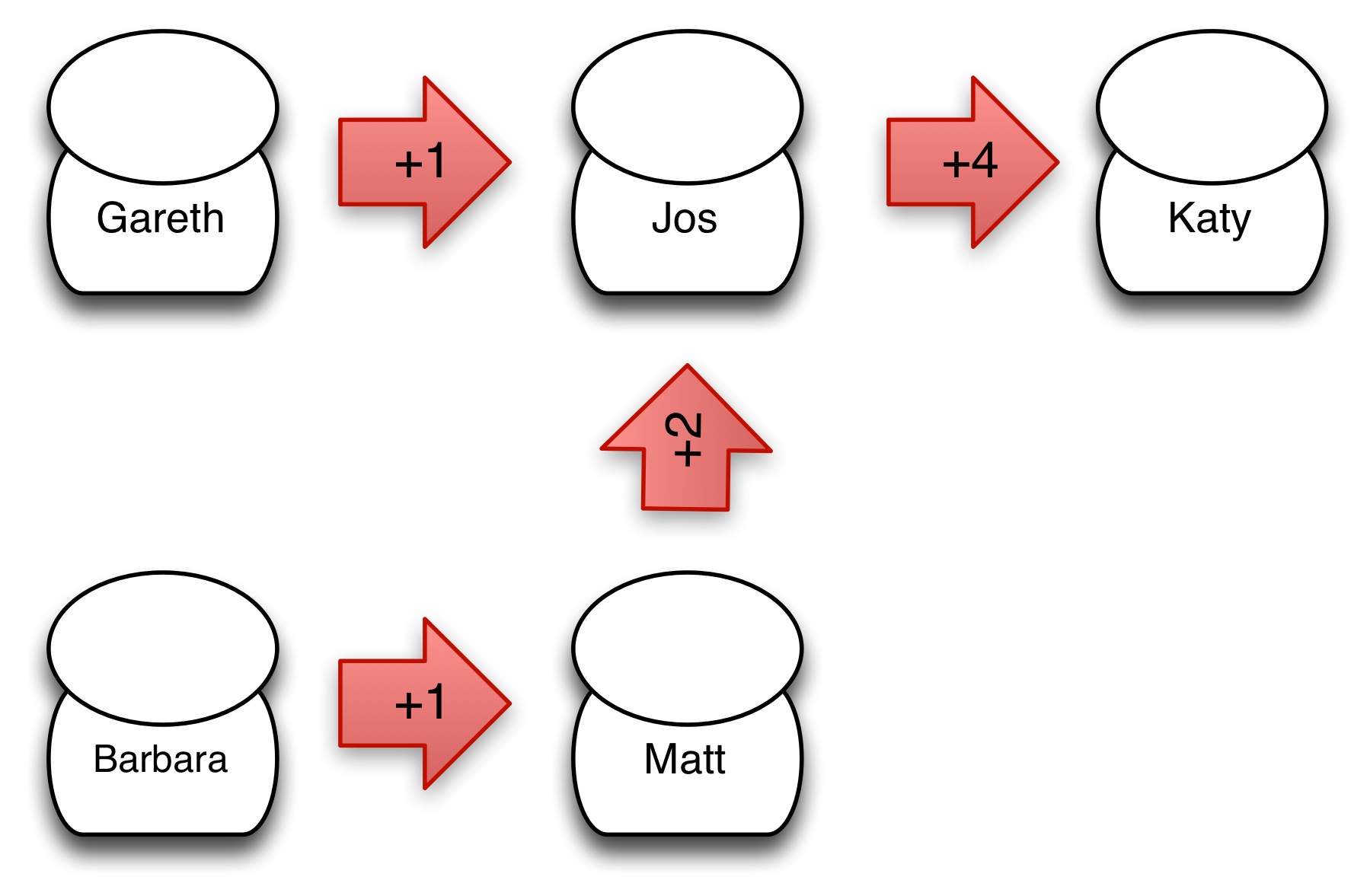

The actors that participated in the MSF were diverse, with close to 200 organisations, networks and groups. Modes of agency were correspondingly diverse. However, the process of ‘midwifery’ was key, giving space for the community to ‘birth’; bring forth its alternatives, agendas and concerns. In this sense agency was facilitating the collaborative agency of others in enacting change – the meaning of ‘meta-formation’.

Modes of agency could also be distinguished into that which was outer focused (change initiatives enacted on the world), and those that were inner focused, (initiatives that aimed to develop and strengthen collaboration and work between the network of actors). Movement building linked the two modalities of outer and inner focus: building the internal strength, knowledge, and capacity for collaboration, and the diverse modes of action used by networks in the enactment of structural and worldly change. Inner and outer movement building is represented by the subsequent figure 1.

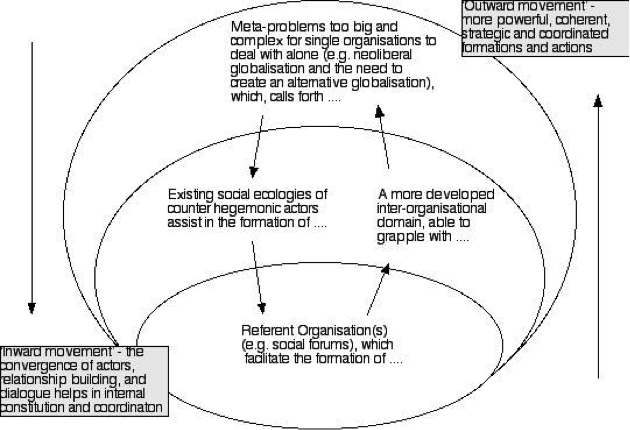

Figure 1: Meta-problem(s) the Development of WSF(P)

Figure 1 shows how the meta-problem represented by the pathologies of neo-liberal globalisation hastened the development of meta-networks of actors, which gave birth to the WSF and satellite forums (e.g. MSF) as ‘referent organisations’. In Trist’s view, the functions of a referent organisation includes, ‘regulation…. of present relationships and activities; establishing ground rules and maintaining base values; appreciation… of emergent trends and issues [and] developing a shared image of a desirable future; and infrastructure support… resource, information sharing, special projects…’ (Trist 1979, 9).

‘Referent organisations’ fill the role of coordinating and holding the space for this new domain of inquiry and action. The diversity represented by the WSF process has confounded many, and yet the domain related meta-problem(s) that actors addressed, however contested and debated, in Trist’s words:

“constitutes a domain of common concern for its members … The issues involved are too extensive and too many-sided to be coped with by any single organization, however large. The response capability required to clear up a mess is inter- and multi-organizational” (Trist 1979, 1).

The forum had modest attendance between 2004 and 2010. Events were held in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009, bringing together an average of between 300 and 400 participants, and hosting between 30-50 workshops per event. The initial forum in 2004 was a one day event (which expanded to two days in 2005). In 2006 the MSF ran the G20 Alternative as part of the G20 Convergence (an aspect of the protest against the G20 meetings then). The year 2007 saw the largest MSF event attendance (with approximately 450 participants). This was followed by a mini forum in 2008, and a larger two day forum in 2009. The last MSF events were held in 2010, and the remaining proceeds from the MSF organisation were given to the “CounterAct: Training for Change” project.[1]

Meta-networking and social complexity

Meta-networking engages both epistemic and ontological complexity. Epistemic complexity refers to the diversity of viewpoints, standpoints and worldviews that converge within a process. Ontological complexity refers to the diverse array of organisations and groups and the issues they address that converge as part of a process. This epistemological and ontological complexity exists as part of what social change processes are (the composition of embodied participation), and as part of what social change processes aim to address (the composition of social issues). This can be seen as inner and outer dimensions of social complexity.

| Internal composition of field (participants) | External composition of social issues to address | |

| Epistemic complexity | The array of ideological positions, cultural standpoints and worldviews that exist in the actors and participants that take part in a process or convergence | The array of ideological positions, cultural standpoints and worldviews that are projected upon the various issues that actors and participants aim to address |

| Ontological complexity | The array of types of actors, such as social movements, NGOs, networks, ethnic groups, diasporic communities, and people as a convergence | The array of issues that actors and participants aim to address, and how they are systemically inter-locked and related |

Table 1: Four Types of Social Complexity

In the next section I will describe the inner (epistemological) and outer (ontological) dimensions of this emerging form of ‘prismatic’ work. The inner dimension refers to the thinking, emotioning and feeling that provide the foundations for this kind of practice. The outer dimension refers to the behaviors, structures and systems that these emerging practices employ.

Epistemic complexity and inner dimensions

In the early days of my PhD work I received some criticism from neo-Marxist colleagues. They saw my writing and, to them, it looked confused, without coherence, lacking a tradition. While I agreed with many of the propositions made by the scholars who have pioneered neo-Marxist analysis into contemporary globalisation (Robinson 2004; Sklair 2005), as an organiser working in projects that brought multiple perspectives together, holding a single discourse (as truth) for whatever we spoke about (globalisation, etc.) was unworkable from a practical point of view. Eventually I needed to engage in a dual movement with respect to well-established scholarship and perspectives on globalisation and its transformations. On the one hand I needed to deepen my appreciation of such perspectives, by attending conferences, talking to proponents and through reading. I needed to appreciate where such perspectives made sense and what they explain well. Likewise I also needed to allow myself to settle into a space and an identity that supported openness and curiosity with respect to various discourses and perspectives.

But it was not all about perspectives, and this was where Latour (2005) was crucial. For Latour, understanding the social was fundamentally about how elements associate. For him the researcher-practitioner should try to not impose pre-existing theories or frameworks on an area of observation. What was needed was a way of seeing how ideas, institutions, machines and people all come together to form and reform the social. This kind of post-materialist empiricism was and is central. It transformed the role of discourse and ideas from that which explains reality (e.g. post-positivist), into that which guides actors in their quest to understand and act – discourse / ideas are embodied and mediate people’s strategic action. An idea’s truth lay more in its utility and enabling effective and strategic action, rather than the presumption of universal or historical law.

The transformation of discourse from truth/false to an element in a Latourian assemblage paralleled another shift. My inner perspective as a practitioner could see connections between various modes of analysis and action of the people that I networked with. There existed a field of thinking and activity which had deep relatedness, but which had not yet been connected. I could see the opportunities in this ‘ecology of knowledges’. The idea of ‘meta-networking’ emerged to guide me (Gilchrist 2004). The meta-networker moves across multiple spaces, sometimes a chameleon, listening and looking for connections between various organisations, people, ideas, projects. Opportunistic and restless, to see the possibility of emergence from what currently exists.

Two metaphors also helped guide this. The first metaphor was of the ‘bee and flower’. The bee and the flower both have unique characteristics (one coming from the insect family and the other from the plant family). Yet at some point a reciprocally beneficial relationship developed, as flowers relied on insects (like bees) to carry their creative genetic material, and bees relied on flowering plants for nutrients. While they do not communicate in the strict sense, they express signifiers that allow for a broader process of structural coupling (Maturana 1998). Their ontogenetic differences do not preclude either the codes needed for structural coupling nor a tacit shared interest. I found in my social work that this complex ‘structural coupling’ occurred across ontological diversities (organisations doing different types of work), epistemological diversities (organisations / groups with different worldviews) and thematic diversities (organisations working in thematically different areas), in creating ‘ecologies of innovation’ and the potential for ‘meta-formation’.

A second metaphor also guided me – the bridge builder. The bridge builder works between and across diverse actors and their different ways of knowing, facilitating their processes of building coherent strategies for change. Whereas the bee and flower signifies that it was in-and-across the landscape of systems where creative synergy was to be found, the bridge building metaphor was about the practitioner. It indicated that someone needed to provide the unique leadership to bring different elements / people together. The bridge builder created the spaces, platforms and language for people to relate across their diversities. The bridge builder’s inner resources are key: cognitive mapping, to understand a broader spectrum of commonality that has the potential to connect disparate actors toward common goals and projects. In this regard, the practitioner’s capacity to identify hegemonic and counter hegemonic knowledges is critical.

The diverse field of alternative globalisation actors represented knowledges which have been marginalised or obscured by the dominant and official liberalist discourse on globalisation (as inevitable, necessary, progressive, developmental, etc.). Santos (2006, p. 13) argues it represents an ‘Epistemology of the South’, which expresses the legitimacy of the (multiple) knowledge systems of the world’s marginalised and the social experiences which inform them. Whether they be Latin American indigenous groups struggling against the incursions of trans-national corporations, African peasants struggling against subsidised agricultural imports, Dalit (untouchables) struggling against an Indian caste system, Cuban or Australian permaculturalists, Buddhists teaching meditation for peace, or climate scientists arguing for the de-carbonisation of the global economy, together they represent knowledges coupled to diverse experiences, which challenge hegemonic expressions of neo-liberal globalisation and reality. In short, identifying counter-hegemonic discourse and knowledges was and is fundamental to the bridge building efforts needed to create critically informed social change.

Ontological complexity and outer dimensions

An approach to the practice of meta-networking for social change cannot just rely on inner resources of practitioners, there are also the ontological dynamics and factors that accompany any effort that critically informs strategic action.

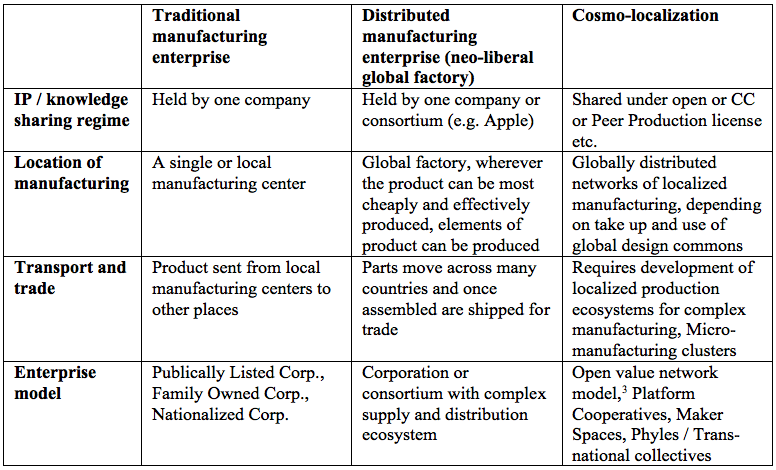

In my work I found that the recognition of the dynamics of power was central to informing my own reading of strategy. As the movements for another globalisation are fundamentally concerned with both politicising and transforming power structures (Teivainen 2007), we need ways to think about what structures of power mean in respect to globalisation. For example, in Sklair’s (2002) analysis, the current global system is composed of three main spheres of power, the economic, political and cultural, and through this we witness the emergence of structural synergies of domination. This is carried forth economically through transnational corporations, politically through an emerging transnational capitalist class, and culturally through the ideology of consumerism (Sklair 2005 pp. 58-59). As Mills (1956) explored half a century earlier through his analysis of the circulation of power in the US between economic, military and political domains, Sklair also points out the emerging structural synergies in capitalist globalisation. Korten (2006), in a similar fashion, points out his vision of needed structural (cultural, political, economic) alternatives. In Table 2 I use both Sklair’s and Korten’s distinctions as examples of how alternatives presented within the alternative globalisation movement are structural in nature.

| Capitalist globalisation (Sklair) | Alternative globalisation in AGM (Korten) | |

| Economic | Trans-national corporations and their interests; | Local living economies,

Fair share taxation and trade, Democratising workplaces; |

| Cultural | Culture-ideology of consumerism – worth based on possessions and accumulation; | Post patriarchy feminine leadership,

Narratives of an Earth community, Spiritual Inquiry; |

| Political | Trans-national capitalist class – plutocratic systems of governance. | Democratising structures of governance,

Participatory and open media, Precautionary policy making. |

Table 2: Capitalist to Alternative Globalisation, Sklair (2002) and Korten (2006)

I discovered that social alternatives did not exist in the somewhat ambiguous territory of (global) civil society, but are directed at a variety of structures (Sklair 2002 p. 315; Robinson 2005). For counter hegemonic alternatives to have the possibility of becoming social realities, this necessarily required that institutional anchors needed to be created across spheres of power (economic, political and cultural). My traditional role as a culture worker / academic / researcher was being challenged, I would need to engage across both the political and the economic. My reading of power also necessitated a reading of counter power. Counter hegemonic alternatives form through new strategic couplings across these domains, such that a field of self-sustaining counter power may become resilient and influential in democratising core aspects of institutional life. My work became consciously about interlinking social ecologies and meta-networking which facilitated alternative formations of structural power. It needed to express a ‘critical’ methodology in building social capital, by opening up opportunities for interaction, informational exchange and collaboration as a counter point to elite forums of social capital development (e.g. the Davos World Economic Forum) (Gilchrist, 2004 pp. 4-7; Mayo 2005, p. 50). Importantly, the imperative to work across the domains of business, politics / policy, and culture (media / academia) further reinforced the need to integrate the three levels of structural, poststructural and the commons, as social change was identified more concretely with power structures, and yet the discourses across different power structures are diverse, and within this were potentials for identifying commonality and opportunities for collaboration.

Three ‘Ps’ are critical in the practice of meta-networking: processes, platforms and places. When bringing people together across diverse domains of social experience, there needs to be a place that can not only accommodate that diversity, but which can leverage or harness diversity toward mutual recognitions, common themes, strategic opportunities and collaborative action. People need places to meet that are safe and nurturing. Social spaces can be analogised with geographic spaces. Some are fertile ground to plant seeds, while others are deserts. In the early days of my organizing, I was assisted by places like Borderlands, Ceres, Trades Hall, public libraries and other locales, many which had a history of innovating social change and were themselves examples of counter hegemonic alternatives. Later, my projects had to have more systematic approaches to procuring spaces.

Platforms are structures that allow participants of a particular process to cohabitate for a time. Platforms are by design and can be created for a number of different purposes. They can be both live and / or online, and ideally both. In my work with the MSF, we took the lead from the global organisation and followed the open space method (Owen 1997). The open space method allows participants to design and develop their own thematic ideas and sub-processes. It is less programmatic and more diverse and divergent than traditional conference processes. Using open space we would host about 300-400 participants and approximately 30 workshops, mostly developed by participants. Participants would choose which workshops they wanted to attend. While open space helped to accommodate diversity and make critical connections, it did not necessarily facilitate collaborative or strategic action across the whole. Platforms are in a sense a convergence of a space and a method for people to come together in a particular way. Online platforms have developed substantially over the last 10 years, and there are now many options.

Process and methodology, which is entangled with both space and platform, is still an important distinctive element. Action researchers have developed a wide variety of approaches to large scale group intervention, such as search conferences, as a way of engaging in large-scale and systemic collaborative inquiry and action (Martin 2001). Recently methodologies include Collective Impact, developed in the United States (Kania 2013), and Living Labs, developed in Europe (Beamish et al 2012). These various approaches recognise that beneficial social change and innovation must connect across diverse sectors, harness and leverage diverse participants perspectives, capabilities and resources, and build common ground for collective action and collaborative innovation.

When working with social complexity, I have learned that understanding the nature of the social complexity, the amount of time people have to come together, where they come together, and under what explicit or implicit motivations people come together, all matter. This requires preparation and a willingness to explore and research various participants and their backgrounds, and to begin to build the groundwork for a process that will genuinely serve the interests of people who engage, and which will create the possibility and opportunity for collaboration and innovation. These three ‘Ps’, processes, platforms and places, are all of fundamental concern in building meta-networks for positive social change in conditions of systemic complexity.

Conclusion

In my own work an approach that posits the structural and post-structural as opposite binary positions is less useful than one which brings them together toward building common ground (the commons) toward critically informed social change. An approach that recognises the legitimacy of a diversity of viewpoints and discourses is an important aspect of social and community work in the 21st-century. We live in a world in which more people from different backgrounds are coming together at various scales and geographies. Increasingly we work across multiple cultural reference points. At the same time, the idea of ‘wicked problem’ has taken root, and we understand that the most intractable issues cannot be solved by solo stakeholders who are isolated from the vast majority of people and actors who inhabit those same ‘wicked systems’. We need well developed practices of meta-networking that can build common ground between diverse actors to solve complex social problems. We need a whole of system approach that brings people together from across the systems in need of change. While this is very different from traditional service delivery modes of engagement, deeper change requires systemic inquiry and action. Given the cultural and structural complexities we are increasingly engaged with, poststructuralist approaches and perspectives are needed to engaging with multiplicity, transforming diversity into a resource for systemic and collaborative innovation. At the same time, however, differing perspectives are necessarily mutually exclusive. There is the relational in-between – our commonness, common humanity, participation in a commons and the active development of common-ground through the practice of meta-networking.

References

Beamish, E. McDade, D. Mulvenna, M. Martin, S. Soilemezi, D. 2012, Better Together – The TRAIL User Participation Toolkit for Living Labs, University of Ulster

Bergmann, V. 2006, ‘Archaeologies of Anti-Capitalist Utopianism’ in Imagining the Future: Utopia and Dystopia, edited by A. Milner, Ryan, M., Savage, R., Arena, Melbourne

Briskman, L. Pease, B. and Allan, J. 2009, Introducing critical theories for social work in a neo-liberal context in Critical Social Work, edited by J. Allan, Briskman, L., Pease, B., Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest

Bollier, D. and Helfrich, S. ed. 2012, The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State, Levellers Press, Amherst, MA

Carley, M., Christie, I. 1993. Managing Sustainable Development. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Castells, M. 1997, The Power of Identity, Blackwell, Mass

Chisholm, R. 2001, ‘Action Research to Develop an Inter-Organizational Network’ in Reason, P. and Bradbury, H. (ed.) Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, Sage, Thousand Oaks

Gilchrist, A. 2004, The Well Connected Community, The Policy Press, Bristol

Hamilton, C. 2007, Scorcher: The Dirty Politics of Climate Change, Black Inc., Melbourne

Hansen, M. 1997, ‘Antonio Gramsci: Hegemony and the Materialist Conception of History’, in Macrohistory and Macrohistorians, edited by J. Galtung, Inayatullah, S., Praeger, Westport

Ife, J. 2012, Human Rights and Social Work: Towards Rights-Based Practice, Cambridge University Press, Mass

Inayatullah, S. 1998, ‘Causal Layered Analysis: Post-Structuralism as Method’, Futures, vol. 30, pp. 815-829.

Kania, J. and Kramer, M. 2013, ‘Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity’, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Stanford

Korten, D. 2006, The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, Kumarian Press, Bloomfield

Latour, B. 2005, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Martin, A. 2001, ‘Large-group Processes as Action Research’ in Handbook of Action Research, edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, Sage, Thousand Oaks

Maturana, H, Varela, F. 1998, The Tree of Knowledge, Shambhala, Boston

Mayo, M. 2005, Global Citizens: Social Movements and the Challenge of Globalization, Canadian Scholars Press, Toronto

Mills, C. W. 1956, The Power Elite, Oxford University Press, London

Owen, H. 1997, Open Space Technology: A Users Guide, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco

Ramos, J. 2010, Alternative Futures of Globalisation: A socio-ecological study of the World Social Forum Process, PhD, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane

Robinson, W. 2004, A Theory of Global Capitalism, John Hopkins University Press, London

Robinson, W. 2005, The Battle for Global Civil Society [Online].

Santos, B. 2006, The Rise of the Global Left: The World Social Forum and Beyond, Zed Books, London

Sklair, L. 2002, Globalisation: Capitalism and its Alternatives, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sklair, L. 2005, ‘Generic Globalization, Capitalist Globalization and Beyond: A Framework for Critical Globalisation Studies’ in Appelbaum, R., Robinson, W. (ed.) Critical Globalization Studies, Routledge, New York

Teivanen, T. 2007, ‘The Political and its Absence in the World Social Forum – Implications for Democracy’, Development Dialogue – Global Civil Society, pp. 69-79

Trist, E. 1979, ‘Referent Organizations and the Development of Inter-Organizational Domains’, Academy of Management (Organization and Management Theory Division) 39th Annual Convention, Atlanta, Georgia.