In 2016 I decided to contribute a book chapter on a futures studies perspective on participatory action research, in an ambitious project led by Lonnie Rowell, Catherine D. Bruce, Joseph M. Shosh, and Margaret M. Riel. It was quite a journey. I want to specifically thank them and those futurists that helped me by responding to some survey questions: Luke van der Laan, Ruben Nelson, Anita Kelliher, Tanja Hichert, Robert Burke, Mike McCallum, Aaron Rosa, and Steven Gould. Of course thanks to many many other people who are part of this general movement – people I’ve worked with and learned from who are woven through this text. This is a pre-print draft, and citation of final publication is as follows:

Ramos, J. (2017). Linking Foresight and Action: Toward a Futures Action Research. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Action Research (pp. 823-842). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-40523-4_48

Introduction

For over a decade I have been involved in a unique enterprise, to explore, document and integrate Action Research approaches with Futures Studies. This rather obscure endeavor, which from the outside may seem arcane, for me is core to addressing the great social and ecological challenges we face today. Because of this inner direction, I continue to develop this confluence into hybrid approaches to human and social development.

After a degree in comparative literature and on the back of the experience of globalization living in Japan, Taiwan and Spain, I entered a Masters degree in ‘Strategic Foresight.’ What excited me was the emphasis on systems analysis, visioning, and social change. I was attracted to the idea that a group of people could envision a future they desired and then potentially create it. I entered the Futures Studies field with a desire for transformational change.

Futures studies gave me critical thinking and tools and frameworks for exploring the long term, however a ‘discrepancy’ emerged. Futures Studies clarified the sharp challenges faced by our planetary civilization over the long term. The challenges we addressed were large scale and historical in dimensions, what Slaughter (2002) referred to as a ‘civilizational crisis’: long term climate change, casino capitalism and rising inequality, profound shifts in technology, and other issues. The gap for me related to a question of empowerment. Where and how do we discover agency in creating the world we want? Futures Studies gave me knowledge for forecasting, deconstructing, analyzing and envisioning our futures. But I needed to know how to create change.

Intuitively, I began looking for approaches that would address this gap. When I found action research, I was immediately inspired by the diversity of thinking, approaches and case studies and began playing with the potential overlaps and fusion between the two areas (Ramos, 2002). I also interned with Dr. Yoland Wadsworth, involved myself in the AR community in Melbourne and began to find synergies and opportunities to express the logic of foresight coupled with action through a variety of projects. This work has continued to guide a wide variety of current projects. This chapter details this journey.

The Future as a Principle of Present Action

Slaughter (1995) put forward the idea of ‘foresight’ as a human capacity and quality, in contradistinction to the widespread notion that the ‘future’ is somehow outside us. In sharp contrast to a future state independent of human consciousness, Slaughter located the future in human consciousness, in our human capacity to cognize consequence, change, difference, temporality. The future, he argued, is therefore a principle of present action (Slaughter, 2004). The images we hold of our futures can and should inform wise action in the present.

This simple idea represents a radical departure from previous epistemologies of time, from a fixed and unitary notion of the future to one where ‘the future’ is a projection of consciousness and culture. This embodied and constructivist concept of the future points toward the need to build ethnographic and sociological understandings for how various communities cognize time differently, and how human consciousness and culture mediate decisions and action.

In a number of professional settings, foresight informs action in a variety of ways.

- In the area of policy, governments at various scales are engaged in a variety of decisions, many which will have enduring effects over decades and may be difficult to undo. Policy foresight helps regions to understand long-term social and ecological changes and challenges, to develop adequate responses.

- In the area of strategy, businesses require an understanding of how market, technology and policy shifts may create changes in their operating and transactional environments. Strategy foresight helps businesses discover opportunities, address the challenges of fast changing markets, and develop a social and ethical context for business decisions.

- In the area of innovation and design, foresight can inspire design concepts, social and technical innovations that have a future-fit, rather than only a present-fit. Design and innovation provide the ‘seeds of change’ interventions that can, over many years, grow to become significant change factors, leverage for desirable long-term social change.

The broader and arguably highest role for foresight is to inform and inspire social transformation toward ethical goals (for example ecological stewardship and social justice). In this regard social foresight can play a major role in informing and inspiring social movements and community based social action. Citizens and people from many walks of life have the power to plant the seeds of change, create social innovations, alternatives and experiments that provide new pathways and strategies that can lead to alternative and desirable futures. Foresight can inspire a sense of social responsibility and impetus for social action, at both political and personal levels. In my own life, I have found that as I have cognized various social and ecological challenges, I am compelled to act differently in the present. This has been as simple as using a heater less, changing to low energy light bulbs and installing solar panels, to more entailed commitments like attending climate change and anti-war marches, organizing social alternative events, and even co-founding businesses. The link between foresight and action is at once social, political, organizational and personal, and uniquely different for each person.

Futures Studies’ Road to a Participatory-Action

Like any field, Futures Studies has undergone major shifts over its 50-year history. From my perspective as an action researcher, and building on the work of Inayatullah (1990) and social development perspectives (Ramos, 2004a), I argue that the field has gone through five major stages: Predictive, Systemic, Critical, Participatory and Action-oriented. From the 1950s to the 1960s, the field was concerned with prediction, in particular macro-economic forecasting, where change was envisaged as linear (Bell, 1997). From the 1970s to the 1980s, the field used various systems perspectives that incorporated more complexity and indeterminacy into its inquiry and scenarios and alternative futures emerged (Moll, 2005). From the 1980s and 1990s, interpretive and critical perspectives emerged that incorporated post-modern, post-structural and critical theory influences, where change was seen related to discursive power (Slaughter, 1999). From the 1990s to the present, participatory approaches have flourished. The most recent shift puts an emphasis on action-oriented inquiry, associated with design, enterprise creation, innovation and embodied and experiential processes (Ramos 2006).

Figure 1: evolution of futures studies from an AR perspective

To understand these shifts it is important to understand the epistemological assumptions that underpin these modalities. In the linear modality, forecasters believed that the future could actually be predicted. Without a relationship to subjectivity or inter-subjectivity, the future was ‘out-there’ and could be known like a ‘substance’ or thing. There were problems with prediction, however, as many were wrong (Schnaars, 1989), and this perspective could not account for human agency or the ‘paradox of prediction’ – once having made a prediction, other people may decide to work toward an alternative future. It could also not account for complexity, that is, that a variety of variables, factors, and forces interact in complex and difficult to understand ways. Hence the systemic modality was born.

In the systemic modality, instead of attempting to predict a single future, systems analysts created complex models that examined the interactions between a number of variables. Trends and forecasts were still used, but instead of assuming a single future, the ideas and practices for creating scenarios emerged. A number of World Models, including Limits to Growth (Meadows, 1972), took this perspective, providing a number of scenarios relying on the prominence of particular variables, and their interactions. A challenge to this arose when World Models and other systemically informed studies emerged that were inconsistent or which contradicted each other (e.g. Hughes, 1985). Research institutes from different parts of the world produced radically different perspectives on the future. This is where the critical modality brings such contradictions into perspective.

In the critical mode, models or systems for future change have their basis in different cultures, perspectives, discourses and interests, as well depending on whether they were from a ‘developing’ or ‘developed’ world perspective. Variables seen as essential aspects of a system, from a critical view, were an expression of discourse and culture, rather than universal ‘truths’ (Inayatullah, 1998; Slaughter, 1999). This is seen in how gendered power dynamics are expressed in images of the future (Milojevic 1999), or when people are caught in someone else’s discourse on the future, and are in-effect holding a ‘used future’ (Inayatullah, 2008). The critical mode questions default futures and develops alternative and authentic futures. The critical mode affirms the importance of questioning the role of perspective, deepened through engagement in participatory approaches.

Whereas critical futures posits that the future is different based on discourse, culture, and disposition, in the participatory mode or process, contrasting perspectives on the future will be present in the same room or group process. The exercise becomes much less abstract and far more dialogical. The challenge shifts to how people can have useful, enriching and intelligent conversations about the future, while still honoring (indeed leveraging) differing perspectives. The participatory mode uses workshop tools and methods that include previous approaches: identification of trends and emerging issues (predictive), scenario development (systems) and de-constructive approaches (critical). Participation forms the basis for generative conversations about our futures, and is a pathway toward transformative action.

An action modality is what emerges from embodied participation. When people come from systemically different backgrounds, the potential for conflict and miscommunication exists, but likewise a group based inter-systemic understanding can emerge, and this embodied and emergent ‘alliance’ is critical in developing the potential to create change. When participants can co-develop new narratives, authentic vision and intelligent strategies, people can feel a sense of natural ownership and commitment. Group based inquiry that leads to collective foresight with an understating of shared challenges and a common ground vision for change, can call forth commitment and action.

Each stage in the process relies on previous stages. The systems modality relies on statistically rigorous trends and data to construct scenarios. The critical modality relies on scenarios as objects of deconstruction. The participatory modality relies on all previous modes to be enacted in workshop environments. The action mode relies on participants to come together to create shared meaning and commitment.

Situating Foresight Work In The Action Research Tradition

The distinction between First, Second and Third person action research, originally developed by Reason and Bradbury (2001a) and Torbert (2001), and now widely adopted in the action research field, is used here to explain the nature of the synthesis of action research and futures studies and helps provide outlines for a proposed Futures Action Research (FAR).[1]

According to Reason (Reason, 2001b), First Person AR concerns a person’s self-inquiry, self-understanding and self-awareness in a research process “to foster an inquiring approach to his or her own life (p. 4)” … and by extension, practice. Second Person AR involves inter-personal inquiry, where people create learning with each other, and is “concerned with how to create communities of inquiry” (p.4). Third Person AR engages in processes for developing co-inquiry at a-proximate scales which may be “geographically dispersed” (p.5) and impersonal.

First Person Futures Action Research

A first person action research approach to futures research entails questioning and transforming one’s own assumptions about the future, as well as one’s practice. As researchers we hold assumptions about the future that, when we engage in fieldwork with others, are likely to change. ‘Data’ here entails documenting and explicating one’s assumptions, intentions and experiences. This can be done for oneself to facilitate self-learning, but also for a project reference group as an aspect of double and triple loop learning (Torbert, 2004). Documenting the revolutions in our own thinking about the future is a critical aspect of any futures research. And, as practitioners engaging in social change experiments with others, we can learn what worked well, not so well, and how we might improve our own practices.

Developmental psychology is employed by Slaughter (2008) and by Hayward (2003) as a way of shedding light on practitioner disposition, and to help practitioners to engage more effectively with the breadth of developmental orientations. Inayatullah (2008) uses the Jungian inspired work of Hal and Sidra Stone (1989) to shed light on the critical factors driving the behavior and psychology of practitioners. Kelly (2005) developed one-on-one reflective processes using student journaling with first year engineering students to facilitate sustainability consciousness and global citizenship (Kelly, 2006). Inayatullah (2006) has been exemplary in generating self-understanding within futures studies.

Second Person Futures Action Research

The second person dimension is the inter-personal experience of a group of people inquiring into and questioning the future together, in a process that leads to actions / experiments that drive further learning and knowledge. Groups will inquire into the nature of the social changes (trends and emerging issues) that may impact them, create shared visions for change, and develop strategies and plans to enact this. When visions, plans and strategies are enacted, effects can be observed and documented (what happened, whether they worked or didn’t, etc.), the experience of which is leveraged to generate new understandings and new actions. ‘Data’ here includes what people express together (e.g. workshop notes) when questioning the future, as well as the documentation of plans, actions and effects that arise from such inquiry.

There are a number of foresight practitioners who have worked with organizations engaging in ‘full cycle’ processes of research.[2] Some of the best examples include the work of Inayatullah (2008), List (2006 ), Stevenson (2006), Kelleher (2005), and Daffara and Gould (2007).

Third Person Futures Action Research

The third person dimension reflects the dynamics of a larger community of co-inquiry. Large-scale processes are used to facilitate and capacitate co-inquiry and action for communities or networks that can involve hundreds or even thousands in inquiry into the future that leads to various types of actions ( e.g. innovation, policy making, art, design and media).

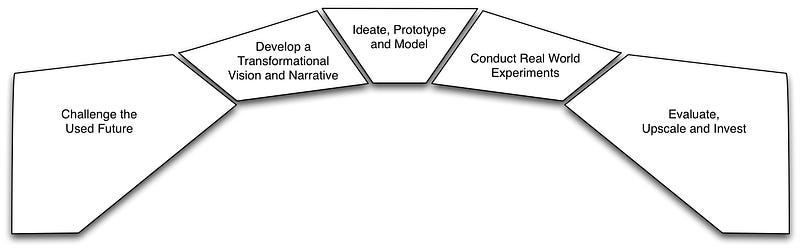

The Anticipatory Democracy projects in the 1970s, which engaged citizens in large scale futures exploration and political / policy change processes across a number of US states (Bezold, 1978) provided early examples of the third person dimension. More recently, select governments have invested heavily in inter-departmental foresight systems that link hundreds of people in foresight informed policy development (Habegger, 2010). Transition Management is exemplary in bringing together long-term sustainability thinking with innovation oriented alliance building across government, business and community. The iteration cycles described in transition management are similar to cycles of action research.

Figure 2: Transition Management Cycle based on Loorbach & Rotmans (2010)

Most recent are web-based / network form approaches to facilitating large scale participatory futures inquiry (Ramos, 2012). These are newer and hold promise in their ability to create large-scale social conversations and interactions concerning our shared futures and challenges. The vision for a ‘Global Foresight Commons’ is another example, where a planet wide conversation about our shared challenges and issues is created that fosters globally networked collaborative projects for change (Ramos, 2014).

Integrating First, Second and Third person modes

According to Reason, these distinctions should not be seen simply as ways to categorize action research practices, but rather as interacting dimensions of these practices that, when used together, make it holistic (Reason, 2004). There are two main avenues for integration. First, we can use the distinctions when making sense of research data, as a method of triangulation. Secondly, the three categories provide a generative dynamic for action research projects to evolve and develop (Reason, 2001b).

Figure 3: ‘Triangulating’ futures action research

Triangulating futures research across these three domains of experience entails observing and noting patterns, connections, synergies and contradictions in the ‘data’ between the distinctions. As action researchers, we should not just be looking for second and third person support for ideas and assumptions by ignoring contradictory empirical or testimonial evidence. This requires critical subjectivity and self-questioning, looking for how second and third Person dimensions may contradict our first person assumptions, imaginings and intuitions about the future, not just support them. This type of research then allows each of the three dimensions to transform the other. Second and third person modes can challenge the inner narrative / assumptions / image of the future of the researcher. First and third person modes can challenge our engagements with others, what questions we ask, what processes we run, and how we interpret what others are saying about the future. First and second person modes can challenge our engagement with the literature on the future, and help guide us in new directions, or to address gaps in the literature.

Synthesis of Action Learning and Futures Studies

Burke, Stevenson, Macken, Wildman, and Inayatullah (with numerous other collaborators) initially pioneered Anticipatory Action Learning (AAL) (Ramos, 2002) . They were steeped in participatory development traditions, as well as humanistic and neo-humanistic Futures Studies. Their vision for this fusion was to bridge a transformational space of inquiry, the long term and planetary future, with the everyday and embodied world of relating and acting. Arguably, their agenda was to engineer a new modality for local and planetary transformation, opening the structural (long term and global) to the question and indeed praxis of participatory action and agency.

Figure 4: Positioning AAL in knowledge traditions (Inayatullah 2006)

Inayatullah (2006) AAL is described as originating from three influences:

- Development oriented participatory action research

- The work of Reg Revans (2011)

- Futures Studies

Inayatullah modified Reg Revans’ formula of learning from ‘programmed knowledge + questioning’ to a future-oriented ‘programmed knowledge + questioning the future’.

Questioning the future entails unpacking and deconstructing the default future, or what has been described in this chapter as a ‘used future,’ our unquestioned image or assumption of the future, whether for our world, organization or ourselves. Challenging this default future, we are then able to imagine and articulate alternative and desired futures. Questioning the future entails a variety of categories – possible, probable and preferred futures – and lays the foundations for discovering collective agency, the future people choose to create. Agency also means that expert knowledge and categories for the future are not automatically privileged; participants can draw from experts, but equally use their indigenous / endogenous epistemologies / ways of knowing as pathways toward creating authentic futures (Inayatullah, 2006, p.658).

AAL represents an evolving and mature theory and practice, with a growing body of practitioners. One of the most important expressions of AAL has been through the development of the ‘Six Pillars’ methodology, a structured yet participatory format for exploring the future. Its strength lies in its simplicity. It features easy to use tools that the non-initiated can easily grasp, and follows a logical sequence that moves participants through various stages: “mapping, anticipation, timing, deepening, creating alternatives and transforming” (Inayatullah, 2008, p. 7). Participants can decide to re-order the tools, even modify them. However, they provide a basic scaffold for what is otherwise a complex and challenging undertaking. Making the exploration of change both enjoyable and empowering should be seen as a significant achievement. Six Pillars can be seen as a ‘practitioner action research’ project where Inayatullah and colleagues experimented and developed approaches over several decades with thousands of people, looking for and discovering what works with groups (Ramos, 2003).

Anticipatory Action Learning’s Disruptive Role

One of the key features of anticipatory action learning is the importance of post-structural and critical theory in the practice of ‘questioning the future.’ One of the central principles is that ‘the future’ is often the site of a hegemonic discourse, that is, ‘the future’ may be an instrument or artifact of power. Thus one of the critical questions asked in conversations is ‘Who is privileged and who is marginalized in a discourse on the future,’ or ‘who wins and who loses in that future’ (Inayatullah, 1998). This follows an argument made by Sardar (1999) that the future has already been colonized, by which he meant that most people’s image of the future has already been set and shaped by powerful interests. These ‘used futures’ maintain their power by virtue of never being questioned. Discovering agency therefore begins with a de-colonization process, where the constructs of the future people unconsciously hold can be questioned and people can generate new, more relevant, intelligent and more authentic visions that empower and inspire. Good futures studies therefore follow what Singer (1993) described as philosophy’s central role: challenging the critical assumptions of the age.

Contemporary Issues in the Confluence of Action Research and Future Studies

In writing this chapter I have consulted with some of the practitioners and networks in the field combing action research and future studies.[3] The following is not a comprehensive list, however, here are some of the critical issues emerging among those at the crossroad of these approaches.

Foresight Tribes

As described in this chapter, the shift from the future as ‘out there’ (the positivist / post-positivist notion of temporality) to the future as ‘in here’ (a constructivist idea of foresight) is a foundational shift in epistemological orientation. Participatory workshops and engagements which begin with questioning the ‘used future’ and exploring peoples not-so-conscious assumptions embark us on a new path of exploring and understanding the embodied and associational dimensions of how we collectively hold visions of change. In my research I have identified distinct ‘foresight tribes.’ Foresight tribes are features of a network society dynamic, where ideas and images of the future are held trans-geographically and a-synchronously (Castells, 1997; Ronfeldt, 1996). Contemporary popular visions are associated with globally distributed communities, where language emerges into patterns for cognizing change. Foresight tribes are both embodied and virtual communities that produce and reproduce particular outlooks, language and images of the futures. Some, like ‘re-localists’ approach the future through the lens of peak oil, an unsustainable global financial system and the looming threat of environmental collapse. They argue we need to begin to build resilience into our locales, relocalize economic processes, governance and culture. Other tribes like ‘transhumanists’ believe we are on the cusp of transforming the very definition of humanity, as artificial intelligence, biotechnological enhancements, and cybernetic augmentation become prevalent. Through my research I have studied and documented over a dozen ‘tribes,’ and have come to appreciate how what is conventionally understood as ‘the future,’ is rather an image of the future held by a community and an expression of associational embodiment and cultural dynamics (Ramos, 2010).

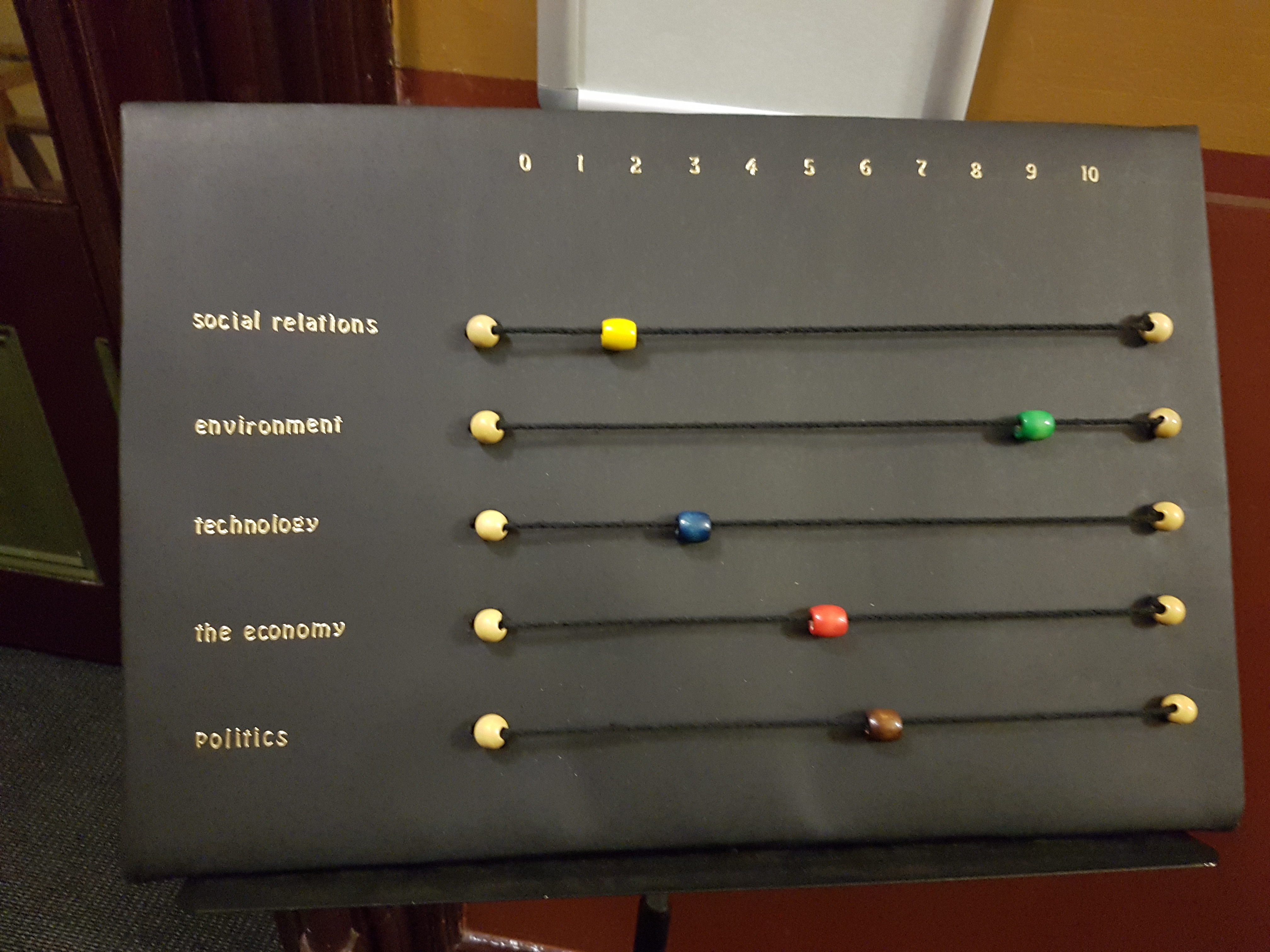

Figure 5: Social change and cognition analysis framework

Actor Network Theory (Latour, 2005), which has strong resonance with Action Research, has been an important methodology I’ve used in decoding discourse within tribes. Discourses can hold notions of temporality, both of the past (how we got here) and future (where we are going). A discourse also holds key notions of structure (what is real and enduring) and agency (who / what has the power to create change). Underpinning both is an epistemological dimension, who and what is legitimate in respect to knowledge of social change. These different discourses give rise to distinct notions of strategic action. Thus, theories and discourses for change do not necessarily explain reality; they explain what ideas are held by people that guide their notions of correct action – why they act in particular ways. As Van der Laan (Personal Communication, October 2014) remarked ironically, “Action is based on deep assumptions which create systems of the future” – rather than explaining the future, these discourses generate modes of strategic action that help to shape the future.

Narrative Foresight

People’s experience of reality is mediated through myth, metaphor, story and narrative (Inayatullah, 2004; Lakoff, 1980; Thompson, 1974). In this regard, supporting change requires helping organizations and communities to generate new narratives. For Inayatullah it is an essential step, where participants use ‘causal layered analysis’ to deconstruct existing (static) narratives and develop new (empowering) narratives for themselves. Some are using the new field of ‘trans-media storytelling’ to engage participants in co-creating narratives within a developed story space for many types of contemporary media (von Stackelberg, 2014). Other practitioners have been inspired by the archetypal work of Joseph Campbell in developing participatory foresight processes and workshops (Schultz, 2012). Another emerging practice in the field is called ‘experiential foresight’ and ‘design futures,’ where practitioners provide living and embodied narrative contexts, complete with stage craft, actors and scripts, that participants inhabit for a period of time and which provoke them into questioning the future(s) (Candy, 2010; Dator, 2013). Milojevic (2014) combines narrative therapy and foresight approaches.

Drama and Gaming

Drama is one of the oldest forms of story telling and narrative, with myriad traditions across many civilizations and cultures. In the action research tradition, Moreno’s foundational work developing psychodrama, and Agusto Boal’s (1998) development of socio-drama have inspired many around the world. Following suit, in futures studies new approaches have emerged which draw participants into dramaturgical situations and games. Head (2011) developed an approach called ‘Forward Theatre’, a method for exploring alternative futures through drama, to encourage debate and dialog on hypothetical possibilities embodied through well-crafted narratives and performances. For education purposes in the context of foresight and leadership, Voros and Hayward (Hayward, 2006) developed the ‘Sarkar Game.’ Based on a critique of the Indian varna (caste) system, participants embody one of four roles: Worker, Warrior, Intellectual, and Merchant, interacting using the macro social cycle framework developed by P.R. Sarkar. Inayatullah uses the game in workshops to deepen participants understanding of social dynamics, and the potentially progressive and regressive aspects of each archetype. The Sarkar game is “intended to embody the concepts being discussed…to move participants to other ways of knowing so that they may… gain a deeper and more personal understanding and appreciation of alternatives futures” (Inayatullah, 2013, p.1).

Experiential foresight in the ‘design futures’ tradition also combines drama and gaming in innovative ways. Interrogating the power dynamics inherent in communications technologies, in 2012, Ph.D. students and faculty of the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies (HRCFS) (Dator, Sweeney, Yee, & Rosa, 2013) employed a live gaming platform involving over 40 participants from around the world, interacting in a geo-spatial game-world twining virtual and physical interactions:

At the heart of the game’s content were four alternative futures … using the Mānoa School scenario modeling method. Utilizing four ‘generic’ futures from which to construct scenarios that ‘have equal probabilities of happening, and thus all need to be considered in equal measure and sincerity,’ the content for Gaming Futures evolved into a creative exercise in how to apply gaming dynamics … which required building complex, yet accessible, scenarios within a plastic gaming platform” (Dator et al, 2013, p121).

Gaming futures was preceded by work in experiential foresight, within which participants can inhabit and interact within artistically rich yet sociologically plausible alternative futures (Candy, 2010). The scenario sets are created to be subtle, subversive and fundamentally disruptive of participant assumptions, and they act as provocations for further questioning and action. Rosa has developed ‘Geo-spatially Contextualized Futures Research,’ dramaturgical games which twine ubiquitous / ambient computing / augmented reality with physical interaction. He sees Alternative Futures as a collaborative resource:

The PAR [participatory action research] framework lends credence to the idea that participants are co-researchers, actively engaged in the adaptation of the research itself. As our foundational medium of futures research is the alternative scenario (experiential, interactive, immersive), we must design systems that can be changed, taught, and augmented (Rosa personal communication, October 2014).

Dialogue of Selves

Narrative, drama and role-playing, arguably, engage ancient aspects of the human psyche. We respond to particular roles played unwittingly by those around us and by those actors with greater skill. Two approaches with Jungian origins have strong and useful connections with archetypal notions of temporal consciousness. The first is the work of Hal and Sidra Stone, who have developed a psychological system called ‘voice dialogue.’ The central proposition in their work is that the psyche expresses a multi-vocality of being. Different ‘selves’ have different roles and functions, and depending on the context, some are dominant and some are disowned. Their work is employed by practitioners in visioning processes to deepen and provide more holistic approaches (Stone, 1989). Inayatullah (2008) finds that some groups, when conducting visioning processes, disown key elements, making visions less robust and tenable. For example, a group may envision a strategically robust but pragmatic future, but disown what authentically inspires people – that the vision makes rational sense but will not motivate. Alternatively a vision may be deeply inspiring, but if it disowns the planning, control and financial dimensions of a community or organization, it may be un-operable. The goal then is to create visions that integrate multiple selves: the planner, the artist, the servant, the dreamer, the manager… toward the development of holistic visions that are operable – that is, fulfill needs at multiple levels. In this line of thinking the facilitator invariably invokes or provokes what they disown, ‘the Other,’ and it is the challenge of the facilitator to embrace the Otherness of the moment, as an invitation to learn and develop more fully (Inayatullah, 2006).

Anticipatory Design and Co-creation

In my work I have been guided by a passion and vision to link strategic foresight and action research. In the past, this was conceptualized through the idea of ‘anticipatory innovation,’ and use of existing action research approaches (Ramos 2002, 2004b, 2004c). Later, activism and ethnographic foresight became important manifestations to critically question and revision discourse and strategy (Ramos, 2010). Most recently, the link between design thinking and foresight has become prominent.

A new generation of design thinking is emerging, trans-disciplinary, engaging across art, science and technology, commons-oriented and deeply collaborative and participatory. Service design thinking has become an important approach in the interface between creative industries, enterprise creation and social innovation. Service design both incorporates the use of foresight as leverage in conceptualizing services and innovations in the context of social change, and incorporates a participatory and (design) ethnography orientation so that design is tightly coupled with the needs of end users (Stickdorn, 2012).

The Futures Action Model

I created the Futures Action Model (FAM) over a ten-year period (2003-2013). It was a product of my passion to link present-day action with foresight, and of the many conversations, collaborations and opportunities I’ve had with colleagues and clients / students (Ramos, 2013).

FAM was created as a scaffold to facilitate social innovation and enterprise creation in the context of our awareness of social change and alternative futures. It emerged from the realization that problem solving was not linear, and that a non-linear but logical approach that coupled action and foresight was needed. I wanted to clarify the link between foresight and action, but more importantly facilitate an approach by which people could do both simultaneously, and where one activity complemented the other. I also wanted to de-mystify the process of foresight informed innovation and make it easier to generate breakthrough ideas.

FAM is a nested system that posits four interrelated aspects in the foresight-action nexus.

Figure 6: Basic Futures Action Model (FAM)

The largest (sociological) context is called ‘emerging futures.’ This is the space of social change (emerging issues, trends, scenarios), and from a progressive / activist perspective, the challenges we face.

Within this, the next layer down are the various proactive responses from around the world to that challenge. Thus, if rising economic inequality is the challenge and emerging issue at the top layer, approaches that create economic opportunity for the dis-enfranchised would go in the next layer. The key metaphor here is that we now live in what can be called a “global learning laboratory.” Whereas in the past both the problems people faced and the solutions created may have seemed disconnected, suddenly, in a matter of decades, we are interconnected by problems that look similar or have strong thematic overlaps underlying the processes of globalization.

In the third layer down is the ‘community of the initiative,’ which are the people, organizations, projects, etc. that participants using the futures action model can potentially partner with. They are real people and organizations that may have something to offer the start-up.

The final layer contains the core model of the initiative, this is a solution space where participants can explore the purpose, resource strategy and governance system of an initiative that can effectively address the issue or problem. This is the ‘DNA’ of the idea. An initiative will also reflect a new ‘value exchange system’ between stakeholders that may not have been connected before. This is the ecosystem of partners that makes an initiative viable. The new relationships are facilitated by the initiative – as the initiative pioneers have a ‘systems’ level mental map and understanding – they can see how different organizations and people might connect and exchange value in new ways – or they have an intuition about what relationships might be generative – even though they may not know the exact outcomes.

Futures action model has been used in facilitating youth / student empowerment and enterprise programs, for scaffolding anticipatory policy development processes, personal post-graduate coaching of project development, facilitating enterprise development, and facilitating community based social innovations.

Co-creation Cycle for Anticipatory Design

In addition to the futures action model, the most recent manifestation of my thinking to link design and foresight is a conceptualization of an action research cycle that is specifically tailored to a new generation of social innovators, social entrepreneurs and participatory designers. Reflecting on the often confusing cacophony of my own projects and work, both paid and unpaid, as well as those of colleagues, I began to search for commonalities and elements. This led to the development of an action research / action learning cycle similar to the fast cycle development process of agile software development (SCRUM). The context for this finding included a number of factors: the emergence of the network forums that amplifies idea exchange and opportunities for peer-to-peer collaboration, the experimental dynamics of colliding / integrating fields in science, art and technology which produce hybrid and often chimeric innovations, and the need to seed ideas even while maintaining a pragmatic stance toward earning an income. In this iterative process, ideas foment quickly and furiously, prototypes are developed and tested, connected with potential users who are expected to teach and lead innovators, so that ideas can be adapted and evolved or discarded for better ones.

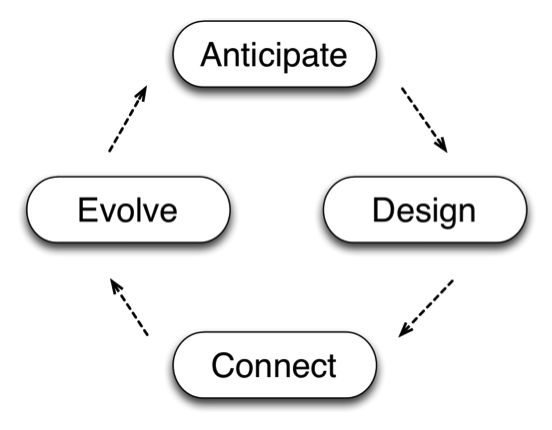

Figure 7: Co-creation Cycle for Anticipatory Design

Anticipate is about the great idea, the what if and what is possible. It is not necessarily about anticipating the big future (futures of society) through scenarios. It is more about what would be great, possible and socially needed now and in the emerging futures (future fit), what can be done with existing and emerging resources / technology, and the kind of future people want to live in (preferred future and values / ethics based).

This leads to the Design, conceptual or physical, of an artifact or model. For example, if dealing with a product, it can be conceptual design, graphic or technical design, or an actual physical prototype. Or if concerning a business, it can be the conceptual business model, or it can be the basic minimum scale of the business in actual form (the Minimum Viable Product offer).

The next phase is Connect, where the design, in whatever its stage, is shared and connected with intended and unintended users. Critical issues focus on usability, value, utility, inspiration and interest by the people who would use the design. Do people like it, want to share it, how well does it work? Connect is similar to David Kolb’s stage of ‘experience’ where the planned experiment is applied and experienced / observed. Because of network society dynamics, however, connect takes on much more meaning, as an idea, design or model can be distributed within a much more dynamic and complex space of engagement. A crowd funding campaign, for example is a typical mode of ‘connect’ in this Anticipatory Design space.

Evolve is the impetus to change the design and offer, try something new, or make adaptations to the existing design. It stems from the experience of connecting, what users of the design (program, project, product, or model) want and need. Depending on the nature of the connecting, the innovators may or may not know what are the best ways to change, improve or adapt it. Learning is critical here – ways that connect the innovator and user – and bring them together into a virtuous cycle of co-creation.

Conclusion: Toward a Futures Action Research[4]

It is in the interest of our many communities and humanity as a whole to develop effective action research and participatory action research approaches to engage in empowering inquiries into our futures. As can be seen from this overview, the outline of such a Futures Action Research (FAR) is still emerging. What we have at the moment are strong overlaps, with a handful of more exemplary and coherent approaches.

Addressing the great challenges we collectively face will require more than just piecemeal innovations. We need to foster a whole-scale social reorientation, whereby taking response-ability for our futures at personal, organizational and planetary scales becomes commonplace. This chapter, hopefully, is a small step in this direction, toward a more coherent and resourced understanding of a FAR approach that offers effective means of transformation in many domains.

References

Bell, W. 1997. Foundations of futures studies Vol. 1. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

Bezold, C. 1978. Anticipatory Democracy: People in the Politics of the Future. NY: Random House.

Boal, A. 1998. Legislative Theatre, Routledge, New York.

Candy, S. 2010. “The Futures of Everyday Life: Politics and the Design of Experiential Scenarios.” Ph.D., Political Science, University of Hawaii.

Castells, M. 1997. The Power of Identity Edited by M. Castells, TheInformation Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Mass: Blackwell.

Dator, J., Sweeney, J., Yee, A., Rosa, A. 2013. “Communicating Power: Technological Innovation and Social Change in the Past, Present, and Futures.” Journal of Futures Studies 17 (4):117-134.

Gould, S. Daffara, P. 2007. “Maroochy 2025 Community Visioning ” 1st Interational Conf. on City Foresight in Asia Pacific Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5-7 September 2007.

Habegger, B. 2010. “Strategic foresight in public policy: Reviewing the experiences of the UK, Singapore, and the Netherlands.” Futures 42:49-58.

Hayward, P. 2003. “Facilitating Foresight: where the foresight function is placed in organisations.” Foresight 6 (1):19-30.

Hayward, P., Voros, J. . 2006. “Creating the experience of social change.” Futures 38 (6):708-714.

Hughes, B. 1985. World Futures: A Critical Analysis of Alternatives. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Inayatullah, S. 1998. “Causal Layered Analysis: Post-Structuralism as Method.” Futures 30 (8):815-829.

Inayatullah, S. 2004. The Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) Reader: Theory and Case Studies of an Integrative and Transformative Methodology. Taipei: Tamkang University Press.

Inayatullah, S. 2006. “Anticipatory action learning: Theory and practice.” Futures 38 (6).

Inayatullah, S. 2013. “Using Gaming to Understand the Patterns of the Future – The Sarkar Game in Action.” Journal of Futures Studies 18 (1):1-12.

Inayatullah, S. 2008. “Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming.” Foresight 10 (1).

Inayatullah, Sohail. 1990. “Deconstructing and reconstructing the future : Predictive, cultural and critical epistemologies.” Futures 22 (2):115.

Kelleher, A. 2005. “A Personal Philosophy of Anticipatory Action-Learning.” Journal of Futures Studies 10 (1): 85 – 90.

Kelly, P. 2006. “Letter from the oasis: Helping engineering students to become sustainability professionals.” Futures 38 (6).

Lakoff, G., Johnson, M. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford Oxford University Press.

List, D. 2006. “Action research cycles for multiple futures perspectives.” Futures

Loorbach, D. Rotmans, J. 2010. “The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases.” Futures 42:237-246.

Meadows, D, Meadows, D., 1972. The Limits to Growth. London: Pan Books.

Milojevic, I. 1999. “Feminizing Futures Studies.” In Rescuing all our Futures: The Future of Futures Studies, edited by Z. Sardar, 61-71. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

Milojevic, I. 2014. “Creating Alternative Selves: The Use of Futures Discourse in Narrative Therapy.” Journal of Futures Studies 18 (3):27-40.

Moll, P. 2005. “The Thirst for Certainty: Futures Studies in Europe and the United States.” In The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies: Professional Edition, edited by R. Slaughter. Brisbane: Foresight International.

Ramos, J. 2002. “Action Research as Foresight Methodology.” Journal of Futures Studies 7 (1):1-24.

Ramos, J. 2003. From Critique to Cultural Recovery: Critical Futures Studies and Causal Layered Analysis In Australian Foresight Institute Monograph Series edited by R. Slaughter. Melbourne Swinburne University of Technology

Ramos, J. 2004a. Foresight Practice in Australia: A Meta-Scan of Practitioners and Organisations. In Australian Foresight Institute Monograph Series edited by R. Slaughter. Melbourne Swinburne University of Technology

Ramos, J. 2013. “Forging the Synergy between Anticipation and Innovation: The Futures Action Model.” Journal of Futures Studies 18 (1).

Ramos, J. 2014. “Anticipatory Governance: Traditions and Trajectories for Strategic Design.” Journal of Futures Studies 19 (1):35-52.

Ramos, J. 2006. “Action research and futures studies.” Futures 38 (6):639-641.

Ramos, J. 2010. “Alternative Futures of Globalisation: A socio-ecological study of the World Social Forum Process.” PhD, Department of Research and Commercialisation, Queensland University of Technology

Ramos, J. and O’Connor, A. . 2004b. “Social Foresight, Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship: Pathways Toward Sustainability.” AGSE Babson Conf. on Entrepreneurship Melbourne, Feb.

Ramos, J., Hillis, D. 2004c. “Anticipatory Innovation.” Journal of Futures Studies 9 (2):19-28.

Ramos, J. Mansfield, T. Priday, G. . 2012. “Foresight in a Network Era: Peer-producing Alternative Futures ” Journal of Futures Studies 17 (1):71-90.

Reason, P, Bradbury, H. 2001a. “Introduction: Inquiry and Participation in Search of a World Worthy of Human Aspiration.” In Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by Bradbury H. Reason P, 1-14. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Reason, P. 2001b. “Learning and Change Through Action Research.” In Creative Management edited by J. Henry. London: Sage.

Reason, P., and McArdle, K. . 2004. “Brief Notes on the Theory an Practice of Action Research.” In Understanding Research Methods for Social Policy and Practice, edited by S. & Bryman Becker, A. (Eds.)(2004), .: . London The Polity Press.

Revans, R. 2011. ABC of Action Learning. Burlington VT.: Gower Publishing.

Ronfeldt, D. 1996. Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks: a framework about societal evolution. Santa Monica, CA. : RAND.

Sardar, Z. 1999. “The Problem of Futures Studies.” In Rescuing all our Futures: The Future of Futures Studies, edited by Z. Sardar, 9-18. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

Schnaars, S. 1989. Megamistakes: forecasting and the myth of rapid technological change. New York: The Free Press.

Schultz, W., Crews, C., Lum, R. 2012. “Scenarios: A Hero’s Journey across Turbulent Systems.” Journal of Futures Studies, September 2012, 17(1): 129-140 17 (1):129-140.

Singer, P. 1993. How Are We to Live? Ethics in an Age of Self-interest, . Melbourne: Text Publishing.

Slaughter, R. 2004. Futures beyond dystopia: creating social foresight. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Slaughter, R. 2008. “What difference does ‘integral’ make?” Futures 40.

Slaughter, R. 1999. Futures for the Third Miillenium. St Leonards, N.S.W.: Prospect Media.

Slaughter, R. 1995. The foresight principle,. Westport, CT: Adamantine Press, .

Slaughter, Richard A. 2002. “Futures Studies as a Civilizational Catalyst.” Futures 34 (3-4):349.

Stevenson, T. 2006. “From Vision into Action.” Futures 38 (6):667-671.

Stickdorn, M. and Schneider, J., ed. 2012. This is Service Design Thinking: Basics, Tools, Cases: BIS Publishing.

Stone, H., Stone, S. . 1989. Embracing Our Selves. Novato Calif.: Nataraj.

Thompson, W.I. 1974. At the Edge of History. New York: Lindisfarne Press.

Torbert, W. 2001. “The Practice of Action Inquiry.” In Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by P Reason, Bradbury, H., 250-260. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Torbert, W., Cook-Greuter, S. . 2004. Action Inquiry: Berrett-Koehler.

von Stackelberg, P., Jones, R.E. 2014. “Tales of Our Tomorrows: Transmedia Storytelling and Communicating About the Future.” Journal of Futures Studies 18 (3):57-76.

[1] Kind thanks to Margaret Riel for offering FAR as a potential name.

[2] I conducted a survey of practitioners in the field in two major foresight networks (the World Futures Studies Federation and the Association of Professional Futurists), asking for survey responses from those who explicitly work across the action research cycle and incorporate various elements of action research. Responses came from Luke van der Laan, Ruben Nelson, Anita Kelliher, Tanja Hichert, Robert Burke, Mike McCallum, Aaron Rosa, and Steven Gould. Much gratitude goes to them all.

[3] This chapter was enhanced from responses to a survey I sent practitioner colleagues in September of 2014.